Review: At Wave Hill, Trisha Brown Dances Fit Right In

The “In Plain Site” program, delayed two days by stormy weather, was worth the wait.

The “In Plain Site” program, delayed two days by stormy weather, was worth the wait.

As part of a digital program presented by the Joyce, the Trisha Brown Dance Company focuses on early movement invention.

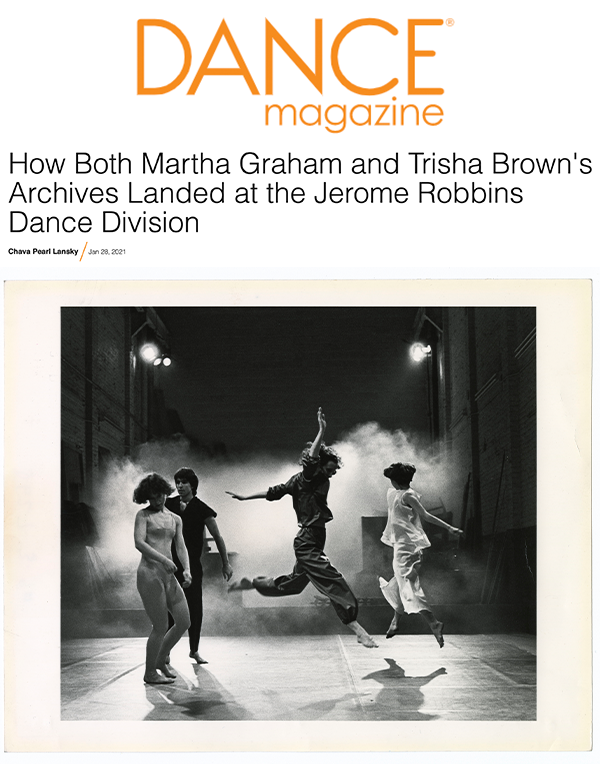

The world's largest dance archive just keeps growing. Over the summer, the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts' Jerome Robbins Dance Division began welcoming two new collections to its illustrious archive. The legacies of Martha Graham and Trisha Brown will be safely housed at NYPL's Lincoln Center campus, featuring rarely seen treasure troves of papers, photographs and moving images.

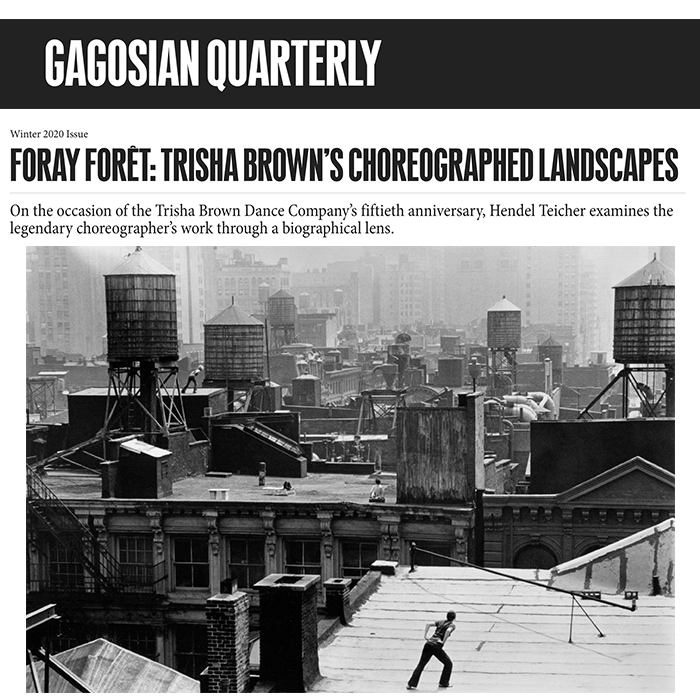

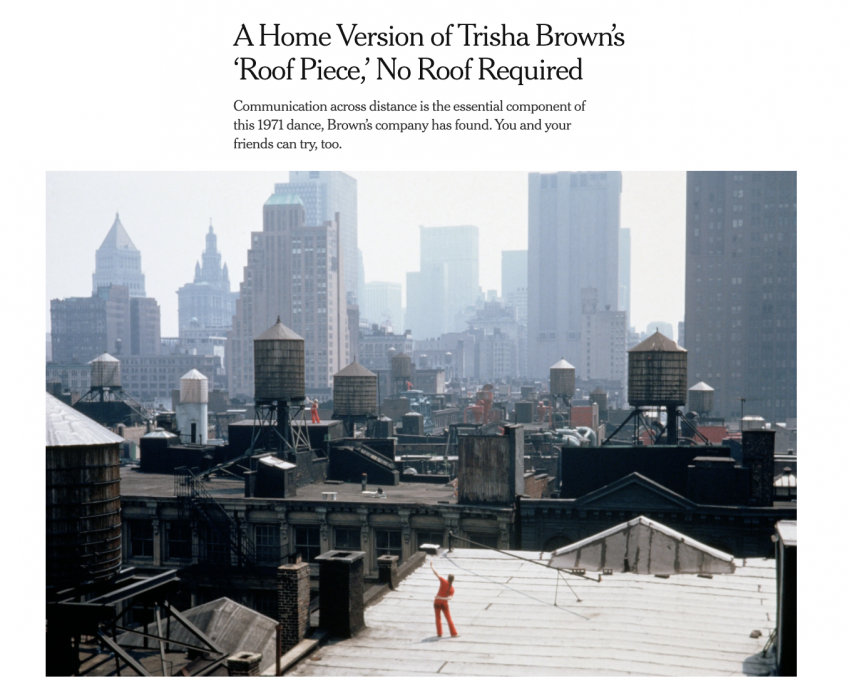

Trisha Brown—one of the most influential choreographers and dancers of her time—spent her formative years in the small town of Aberdeen, Washington, bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north by the Olympic National Forest. The forest spans nearly a million acres and is one of the most diverse ecosystems in the United States, including the largest remaining stands of old-growth trees. The scale and various topographies of that landscape deeply moved and activated Brown’s creative imagination.

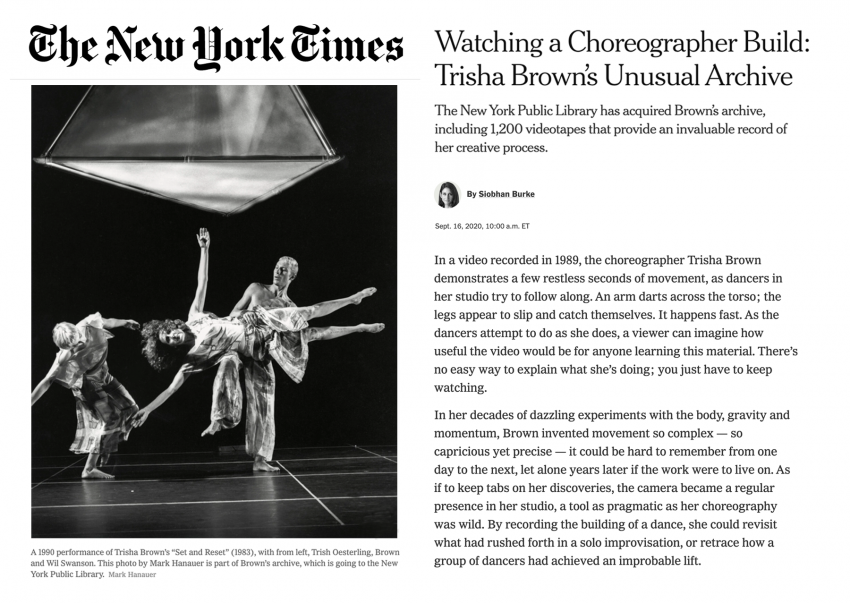

The New York Public Library has acquired Brown’s archive, including 1,200 videotapes that provide an invaluable record of her creative process.

In a video recorded in 1989, the choreographer Trisha Brown demonstrates a few restless seconds of movement, as dancers in her studio try to follow along. An arm darts across the torso; the legs appear to slip and catch themselves. It happens fast. As the dancers attempt to do as she does, a viewer can imagine how useful the video would be for anyone learning this material. There’s no easy way to explain what she’s doing; you just have to keep watching.

The crowd is the first thing I notice in the Trisha Brown Dance Company’s 2016 performance of “Figure Eights” as part of a performance at Seattle Art Museum. The audience clusters behind the row of six dancers, who are all dressed in casual white shirts and loose, white pants. The audience claps and takes pictures, sits stage-side, heads in their hands, on their phones.

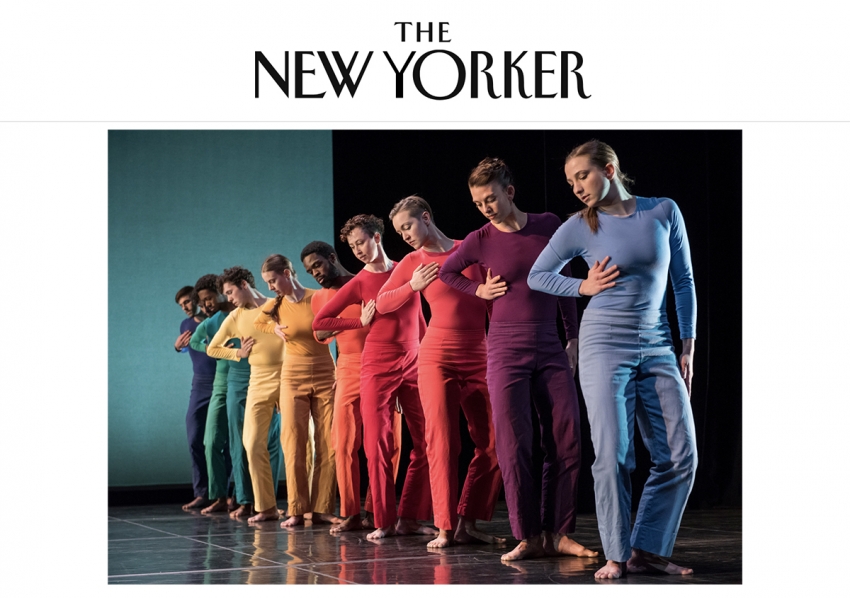

The Chelsea-based Joyce Theatre, one of the city’s principal venues for dance, has begun streaming works by companies who have performed there in the past or, in better circumstances, would have been performing there now. This week’s “JoyceStream,” running April 21-26, features the Trisha Brown Dance Company, currently marking its fiftieth year.

This was supposed to be a big year for the Trisha Brown Dance Company, founded 50 years ago. In early March, the troupe flew to France to begin a sold-out anniversary tour. The first few shows went great. Then came the wave of coronavirus cancellations, and the dancers found themselves on the last American Airlines flight from Paris to New York.

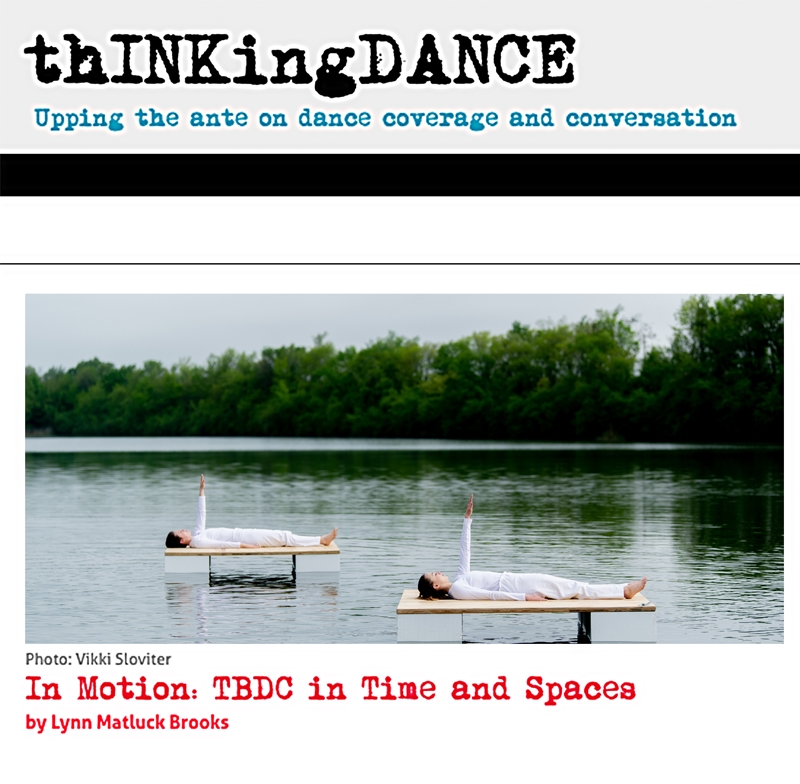

Trisha Brown’s work is more than beautifully sensual, kinesthetically inquisitive, and artistically daring: it also stimulates my mind. I find myself puzzling out Brown’s strategies, asking questions, making discoveries. Two works, Foray Forêt and Raft Piece, performed in close succession at sites in Fairmount Park, offered such delights. I am grateful to the Fairmount Park Conservancy, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage, along with several other organizations that partnered to bring this transcendent afternoon to fruition. Thank you too to the weather gods: a more perfect day could scarcely have been ordered.

At the Edinburgh Festival, five site-specific Brown works proved especially enthralling and poetic.

The five Trisha Brown dances at the Edinburgh International Festival here were, as the title In Plain Site suggests, site-specific: four locations in Jupiter Artland, a contemporary sculpture park 10 miles west of the city’s center. The amalgam of dance and place was revelatory; the dance animated the landscape.